What's that bug?

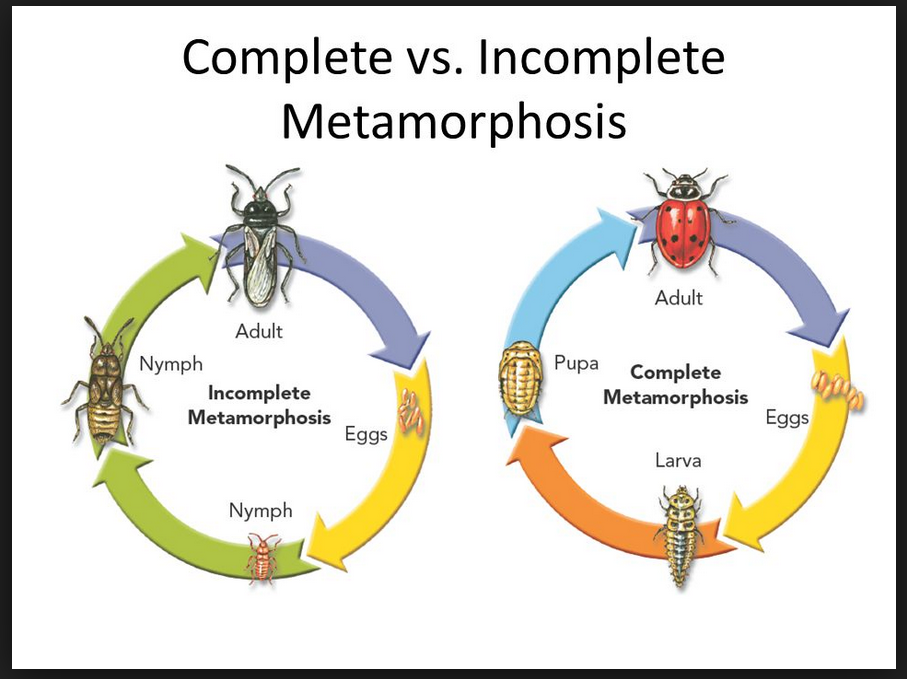

Do not despair, as you are not alone! As you may know, insects are the most numerous animal life form on the planet, comprising about 85% of terrestrial animals. Not only that, insects come in all shapes and sizes, and do magic called metamorphosis after being nymphs or molting their hard exoskeletons as they move through instars on their way to sexual maturity.

"Arthropods are a highly-successful group of invertebrate animals that includes insects, centipedes, millipedes, spiders, mites, horseshoe crabs, scorpions, and crustaceans. In terms of species diversity, arthropods are second to none. That there are in excess of one million arthropods species that have been identified by scientists and there are estimated to be many millions that have not yet been identified. Scientists estimate there may be a staggering 30 million species of arthropods alive today, the vast majority of which are insects."

The insect world is currently divided into 32 orders. The largest order, the beetles (Coleoptera), contains more than 370,000 species. Other major orders are moths and butterflies (Lepidoptera, 150,000 species), bees, wasps, and ants (Hymenoptera, 120,000 species), flies (Diptera, 100,000 species), and bugs (Hemiptera, 80,000 species).

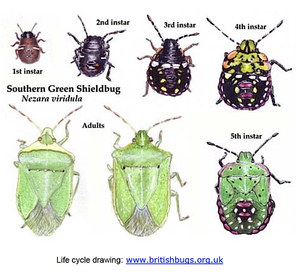

To make mystery bug I.D. even harder, remember that all insects go through metamorphosis-which means that most of them look completely different from adults when they are in their immature stages as larvae and instars-making it quite a puzzle to identify them, since field guides and websites often only show images of the adult stages of many insects.

after three fails (which included an image search, googling "green ladybug", and BugGuide.net), I googled "Seattle pest insects" and found a P-Patch reference document from the Seattle Dept. of Neighborhoods, that told me all about the invasive Green Stinkbug, which were first reported in Seattle in 2014.

Bingo! Lorene's bug turned out to be the 5th instar stage of the Southern Green Stinkbug Nezara Viridula. She found this insect alongside lots of little tiny black bugs (2nd/3rd instar) on a Dalia leaf, never before seen in her garden.

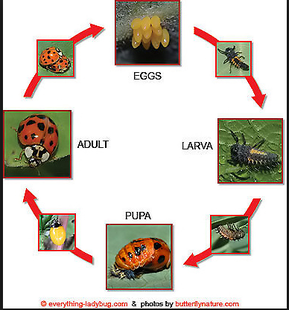

| Mystery bug #2 is the larva stage of the Ladybug Coccinellidae. The first time I found baby ladybugs in my yard, I was pretty sure that I had discovered a new species of insect. Who knew? Insects can go through complete or incomplete metamorphosis. Nymphs are tinier versions of the adults, and instars and larvae can look very different from the adult (think caterpillar/butterfly). To see more examples of insects and their cycles, visit Mr.Science. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed