|

We had both Red Admiral and the Spring Azure butterflies visiting; look how TINY the Spring Azure is, perched on a forget-me-not. The Vosnesenskii bumblebee is our most numerous bombus, and the tiny metallic green bee with striking black and yellow stripes is an Agapostemon, or male sweat bee, a member of the Halictidae family. They are considered solitary but often nest communally in the ground. Also, apparently not good swimmers (I rescued this little guy from the birdbath :^)

0 Comments

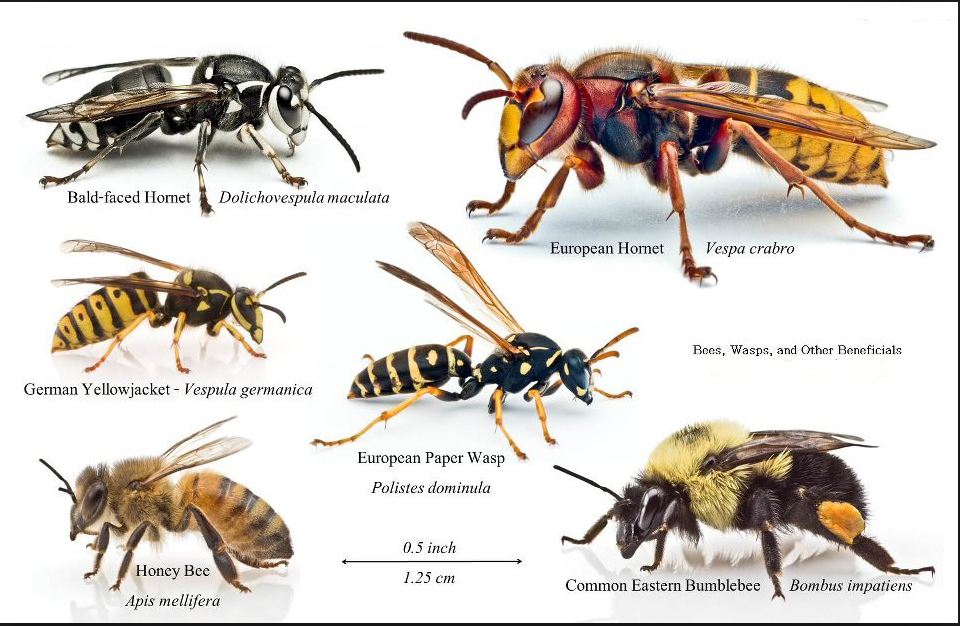

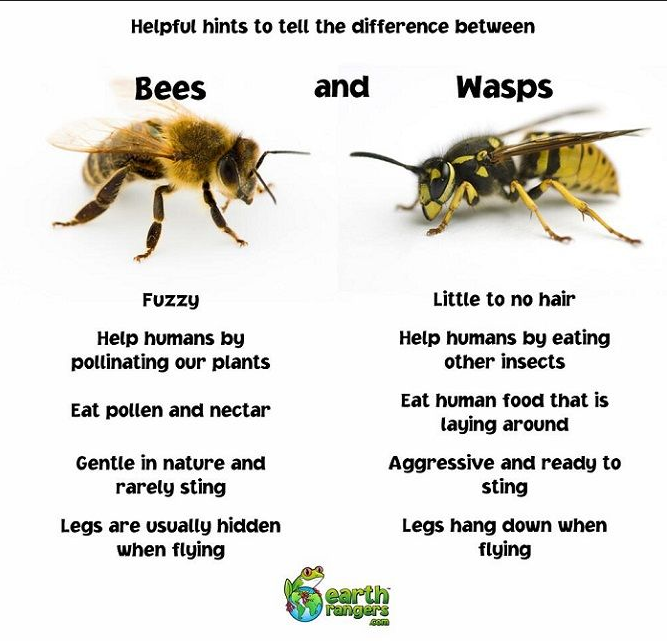

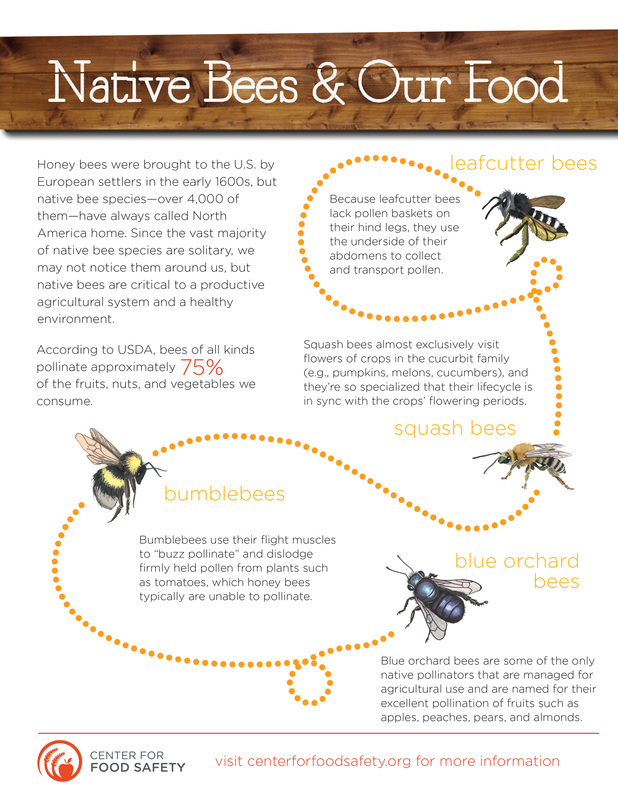

The Difference Between Honeybees and Bumblebees Did you know that there are more than 4500 species of bees that live in the US and Canada, and worldwide over 20,000 species have been identified? Many urban dwellers have not had enough experience with backyard pollinators to easily tell the difference between bees and wasps. For me, it is similar to how you can tell a cat from a dog, or robin from a spotted towhee–not only do they look different, but their movements and habits are unique. You can often ID your backyard bugs by where you find them and what activity they are engaged in. You will find medium-sized golden-brown to black honeybees (photos right) busy flying back and forth between flowers, loading up on pollen and nectar, and zipping back to their hive. Bumblebees (photos left) are generally larger and fuzzier that the honeybee, many with black, orange, or yellow stripes. I consider bumblebees to be the “teddy-bear” of bees, and the most photogenic. Honeybees tend to be sleeker and less hairy than the bumblebees, but both carry pollen on their back legs. Honeybee Swarm Swarming honeybees are docile; they have nothing to protect–as they are merely scoping out the real estate in your neighborhood. The honeybee swarm consists of a healthy queen and upwards of about 10,000 of her workers. Call your local poison-free bee-guy to come collect them, and they will be relocated to a good home. Of all the bees, we know the most about our domesticated non-native European honeybees, not only for their pollination efforts but also for the food, candles, and medicinal products derived from their honey, pollen, wax, propolis, and venom. Honeybees are the outliers in the bee family. They, along with bumblebees, are social insects, which means that they work together in the hive to raise their young and make honey. Most other bees are solitary, do not care for their offspring, and a whopping 70% of all bees live in the ground. Bumblebee nests can be found in the ground, in abandoned birdhouses, or in attics. Their nests are nothing like the honeybee's neat and tidy honeycomb (top); instead, they look really primitive, and a bit cobbled together (below). The bumblebee queen hibernates over the winter, so bumblebees need gather only enough nectar and pollen to raise the brood each season. Honeybees must store enough honey and pollen to allow the workers and queen to survive the winter. Bee or Wasp? Bees: fuzzy, friendly, busy-but not aggressive, flight patterns are direct. Variations in size and color from golden brown to green to black, thick legs with pollen baskets, nectar gatherers; nest in ground, woodpiles, hives, attics, and walls. Wasps and hornets: often aggressive, many carnivorous, striking yellow-black or white-black pattern that shouts CAUTION! Shiny, long thin legs (no fuzz or pollen basket-), wasp-waist, annoying at picnics, zig-zag flight pattern, paper nests found in trees or under eaves. poster by Alex Surcica Want to know more? Check out the book "The Bees in Your Backyard" by Wilson and Carril; for a peek inside my beehives, and more images of the wild things that visit my backyard click here.

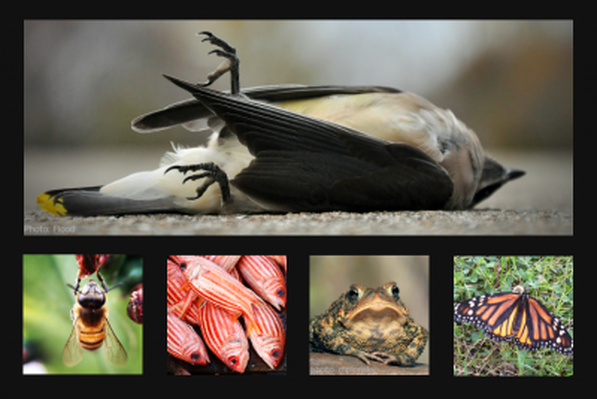

Narrated by Cedar Anderson, the inventor of the FLOW hive. Bonus double-feature for you today :^) also from Flow. Enjoy! Re-posted from the Center for Food Safety Popcorn's Dirty Secret" won the 2015 Digital Edge award! It’s no secret we love popcorn. We Americans consume more than 16 billion quarts of popcorn each year. But we’re getting more than we bargained for in all those bowls of popcorn: bee-toxic pesticides. Bees are dying at alarming rates, and scientists have identified a group of insecticides called neonicotinoids (“neonics”) as a prime culprit in these drastic population losses. The largest single use of neonicotinoids is as a seed coating for field crops (like corn, soy, canola, and wheat). In fact, researchers estimate that 95-99% of all field corn grown in the U.S. comes from seed coated with bee-toxic neonic chemicals. Neonics are the most widely used insecticides in the world. What makes them different from most pesticides is that they are systemic chemicals, meaning they are dispersed throughout the treated plant, rendering the whole plant toxic. Just as alarming, neonics are shown to last in the environment for years, harming species that the chemical was not designed to kill – like bees, butterflies, birds, and other helpful insects. Unfortunately, the popcorn industry uses bee-killing chemicals on their seeds, too. That’s why we’re calling on Pop Secret, one of the biggest brands in the industry, to urge them to source their popcorn from seeds that are NOT coated in these harmful chemicals. Pop Secret would not be alone in taking action against neonics:

The American Bird Conservancy reports that "a single corn kernel coated with a neonicotinoud can kill a songbird", and the Center for Food Safety reports that they are polluting our water systems too. It is ironic to think that man might determine his own future by something so seemingly trivial as the choice of an insect spray. - Rachel Carson, Silent Spring

Our honeybees were abuzz on equinox, gathering pollen and nectar from the borage; I decided to gather borage blossoms as well, for our salad and tea. Not only beautiful, but good for you too.

Today I spotted a Bombus melanopygus queen, out fueling up on nectar and pollen for her winter sojourn underground. After mating in late summer, bumblebee queens hibernate and emerge in the spring to found a new colony. (This is the bee featured in my header and the Xerces poster bee-child)

You can create overwintering sites for bumblebees by leaving leaf litter and uncut bunched grasses in your yard, as well as large sections of untilled soil in your garden. They also seem to favor birdhouses that have not been cleaned out, rock walls, and woodpiles. If you do find an inhabited BB nest, please do not touch it or move it! It will be abandoned at the end of the summer. Xerces would love to hear about the bumblebee nests in your backyard. Infographic for you, on how to create bumblebee habitat. Let's bring 'em back!

Not that the name matters; the bees love the abundant pollen, and we will have plenty of organic sunflower seeds to share with our backyard birds this winter. Our own variety of "ring-of-fire": here we are burning old brood comb and enjoying the hot colors and lovely beeswax aroma. Perfect for a cool summer evening.

Photos © T. Byrne 2015 Perhaps the butterflies read Pacific Horticulture?

We were delighted to have this Lorquin's Admiral Limenitis lorquini make a visit to our backyard. It fluttered between our Stewartia and the Washington Hawthorne, apparently just basking in the sunshine. The adults sip flower nectar from plants (including California buckeye, yerba santa, and privet) and also enjoy feasting on bird droppings and dung (hmmmm, I wonder if the dairy manure compost we just brought in attracted this one?). I do not know if any eggs were laid or if this was just a visit; regardless: it was a welcome sight and a relief from all the Cabbage Whites. Bring on the native butterflies! Action Alert June 17, reposted from Beyond Pesticides: Protecting honey bees and wild pollinators from pesticides Since 2006, honey bees and other pollinators in the U.S. and throughout the world have experienced ongoing and rapid population declines. The continuation of this crisis threatens the stability of ecosystems, the economy, and our food supply, as one in three bites of food are dependent on pollinator services. In 2013, Beyond Pesticides joined with beekeepers and environmental allies in a lawsuit challenging EPA's approval of two neonicotinoid pesticides. These highly toxic, persistent and systemic chemicals have been widely implicated as leading factors in pollinator declines. For a primer on the pollinator crisis, see the lawsuit's Press Release. Also, read the 2013 Lawsuit, Appendix A: Clothianidin, and Appendix B: Thiamethoxam. Click the links below for more in-depth information: Resources and Educational Materials BEE Protective in Your Community Pollinator Alerts For the latest pollinator-related articles, visit Beyond Pesticides' Daily News Blog June 15-21 is National Pollinator Week, and in order to move action forward on the pollinator crisis, Beyond Pesticides and The Center for Food Safety launched the BEE Protective campaign, a national public education effort supporting local action aimed at protecting honey bees and other pollinators from pesticides and contaminated landscapes.

BEE Protective includes a variety of educational materials to help encourage municipalities, campuses, and individual homeowners to adopt policies and practices that protect bees and other pollinators from harmful pesticide applications and create pesticide-free refuges for these beneficial organisms. In addition to scientific and regulatory information, BEE Protective also includes a model community pollinator resolution and a pollinator protection pledge. Pollinators are a vital part of our environment and a barometer for healthy ecosystems. Let's all do our part to BEE Protective of these critical species. (Beyond Pesticides, 6/17/15) If you have been inspired by the Pollinator Pathway® (perhaps you read the article in Popular Science which listed the Pollinator Pathway® as the one of the “25 Best Nerd Road Trips” 2013), and have flown cross-country to see it for yourself, I expect you will be underwhelmed by the dismal appearance of Sarah Bergmann’s highly publicized public art project. As you walk along Columbia Avenue between Nora’s Park and Seattle University…(wondering if you are on the right street) you might find yourself asking “What happened?”

In 2008, Bergmann received her first grant from the city of Seattle: $6,000 to make signs and design one garden in a 12-foot-wide parking strip of her Central District neighborhood. Her idea included a plan for a mile-long pollinator corridor. After seven years, and thousands of dollars of public funding, donations, and volunteer hours, it is hard not to wonder-where did all that money go? Back in 2010, after Bergmann had received her second Department of Neighborhoods grant to transform 16 more parking strips, I used to bike across this route several times each week. As a BeePeeker–an advocate for urban pollinators– I was excited to watch the project develop. I visited the informational display at Seattle’s Olympic Sculpture Park, which explained the importance of urban habitat corridors replenished with native plants to benefit bees and other pollinators. I was curious to see what would happen, and I was both hopeful and enthusiastic for the success of the project. Very soon, I began to have misgivings about Bergmann’s approach to creating her pollinator pathways; the website states “The project is a collaborative effort between the homeowners and the project. It requires buy-in from homeowners to adhere to the program guidelines”, but this is misleading as the original project relied on volunteers to design, plant, and maintain parking strip gardens, rather than on owner engagement and education. The homeowners were asked to “host” a Pollinator Pathway® in their parking strip, and the opportunity was lost to nurture all kinds of enthusiasm and community Biophilia. As a teacher and parent, I knew right away that this was a recipe for disaster and disinterest. Also, rather worryingly, it was explicitly stated on the Pollinator Pathway® website that the public should not disturb the owners or ask them questions about the project! In the beginning, it was clear that Sarah Bergmann was not a gardener but an artist; it has been interesting to watch the development and marketing of both Bergman and the Pollinator Pathway®– as well as the subsequent monetizing of what had begun as a publicly funded art project. The pathway for pollinators was conceived to connect people, landscapes, and pollinators. Bergmann is now touted as an ecological architect and designer and is the sought-after expert on all things pollinator-pathway related. What an opportunity she has to bring resources, links, and information to the public (I thought) with a focus on pollinators and ecological stewardship! Alas, this has not been the trajectory of the project, and instead of inspiring and encouraging homeowners to “simply plant plants that are native to your region, and choose not to use pesticides” (Bergmann FAQs 2015), Bergmann outlines the need for experts, designers, and an ongoing payment plan to become a certified Pollinator Pathway®. Gone are the plant and pollinator ID guides of the original site, and links to garden templates and plant lists from early PR articles now lead to dead-ends: "Well this is embarrassing. The page you are looking for was not found" (Grist, 9/19/12). This doesn't seem right considering they were paid for with public funding. The original Pollinator Pathway® project is disappointing on several counts, with only 20 of the 60 parking strips converted, the interest in this corridor has waned and the project seems to have been abandoned by Bergmann. This is apparent in the rag-tag and forlorn look of many of the parking strip gardens. If you have taken a walk along Columbia Avenue, between 12th and 29th, it is easy to understand why the signs have been removed and why there are few (hard to find) images of the gardens posted on the website. You will also notice that Bergmann has succeeded in creating pollinator pockets rather than an interconnected pathway, ironically undermining Pollinator Pathway®’s own rigorous certification requirements. Bergmann is currently working on cashing in on the certification of the dreaded “pollinator pocket”, and though not encouraging their creation, a certified "pocket" will have the chance to be incorporated into an official pathway in the future. If the point of a pollinator pathway is to heal our fractured relationship with nature while healing our fragmented landscape, then–in order to be successful–homeowners must be invested. It seems that this has been the "problem" with the Columbia Street vision, a lack of sustainable community engagement. The ugly truth is that the Pollinator Pathway® has not achieved several of its underlying goals, and the result is that Bergmann is now soliciting funding (and volunteers) for the long-term maintenance of the one-third completed/abandoned project. Which brings me back to my opening question: Pollinator Pathway® What is it Really About? Though the Pollinator Pathway® began as a publicly-funded Neighborhoods Grant, it has blossomed into something much bigger: a slick corporate Bergman marketing campaign. The term “pollinator pathway” is now a ® registered trademark, and in addition to the initial cost to certify your parking strip as a Pollinator Pathway®, Bergmann will charge a yearly fee for your parking strip to remain certified. There are many ways for the public to support native pollinators, but donating money or volunteering time to the Pollinator Pathway® seems to undermine the opportunity for homeowners to become excited, engaged, and invested in rewilding their own parking strips. Leaving the harsh reality of the failed parking strip project behind, Bergmann has a new & improved version of Pollinator Pathway®, her website–which is an extraordinary example of repackaging and marketing. When visiting the site, I am struck by the lack of information on, or images of, pollinators. In fact, as of today in the main pages you will find: a photograph of a honeybee, a drawing that shows three unnamed native pollinators, and the black silhouette of a butterfly on the original Pollinator Pathway® crossing sign. (Very odd really, when you think about it. And somewhere along the way, the butterfly disappeared. Hmmmm.) Instead of a site rich with information on pollinators, the Pollinator Pathway® website focuses on certification and funding, with a bit of broad and generalized urban planning and landscape design mixed in. The Pollinator Pathway® website does not provide links to websites, books, or other local resources that could inspire homeowners to action and enable them to feel confident in their own ability to provide suitable habitat for urban pollinators. And what about Pollinator Pathway's® commitment to "science"? Strangely, no data on pollinators, such as bug counts (species/numbers), has been published. Bergmann has gained national recognition for her genius and vision and continues to solicit funding for her projects and to promote herself. In July 2014, after announcing the retirement of the “pilot” Pollinator Pathway®, Bergmann stated that her efforts would be now be focused on creating a new partnership and the second "official" Pollinator Pathway® along 11th Avenue. It is easy for you to donate: on the support page you can choose $10,000, $3500, $500, $50, or $20 donation amounts. When I visit Bergmann’s Pollinator Pathway® site, I come away with a feeling of sadness-on one hand she has brought the plight of urban pollinators into the public eye...but, why do I not feel that that pollinators and education are truly the goals of this project? What does it really take to successfully create an urban pollinator corridor? Are certifications and registered trademarks necessary? On the home page of the Pollinator Pathway® website, Bergmann recommends that homeowners engage expert help in order to get started: a landscape designer, a botanist, a native plant expert or entomologist…and that Pollinator Pathway® would be happy to consult with you for an hourly fee. Ultimately, with the branding of the Pollinator Pathway®, Bergmann is capitalizing on what ecologically-aware gardeners have always attempted to do, and what urban landscapers and professional gardeners do everyday: create safe havens in the landscape to support a healthy and biodiverse ecosystem. Replanting your parking strip with native plants and pollinators in mind is an achievable goal for the committed homeowner. I strongly encourage gardeners to take the long view when considering what their goals are and to plant for future generations, as healing our fragmented and degraded landscape takes both time and understanding. I invite you to take a walk around Seattle’s Capitol Hill neighborhood, where you will see a plethora of parking strip gardens, garden boxes, and pollinator corridors. Over the last twenty years, my husband and I have been caretakers of our own backyard wildlife sanctuary and we have gained the satisfaction of researching, designing, purchasing, and planting an arthropod-friendly parking strip. In the process we have become more knowledgeable about the habitat needs of native plants, fungi, bugs, birds, and other small creatures that find refuge in our un-certified pollinator plantings. As a result we have become more intimately connected to our landscape and we take great delight and find solace in our garden. As an advocate for Backyard Wildlife Habitats, urban wildlife corridors, and all the inhabitants of our neighborhood ecosystems, I encourage you to rewild your parking strips in a community effort to make our neighborhoods more beautiful, biodiverse, and arthropod-friendly! Wondering where to start? Please visit my Biodiversity and Biophilia page for resources, and courtesy of Nancy Seiler and the US Forest Service, a pollinator and native plant gardening guide for you to download and share~ |

AuthorTracey Byrne~ Categories

All

Archives

December 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed